FRANTIŠEK GEISLER

František Josef Geisler was studying agriculture at Brno University, when Hitler's troops invaded Czechoslovakia in 1939. Determined not to fight in the armies of the Third Reich, but against them, he was one of many who fled their country with the intention of joining Allied forces. Escaping through Slovakia, Macedonia, Syria, Egypt, Algeria and France, to enlist in the newly formed Czechoslovak Brigades of the French Army. When France fell František Geisler was one of many who left from Agde, on the Mediterranean coast. They sailed in freighters bound for Gibraltar, then Liverpool.

By 1941, the agricultural student had joined both the Free Czechoslovak Forces and the British Army. His military service took him back to occupied Czechoslovakia and occupied France. In 1943, Lt. Geisler was billeted in Dovercourt and there he met the pretty British Wren, Joyce Locke, who became his wife. She left the Wrens, happy to be Mrs. Geisler, and spend the times her new husband had in England, with him.

In July 1944 it was decided that the 2nd. Czechoslovak Parachute Brigade and other Czechoslovak forces join with Soviet Russian Divisions to attack the Germans from the East and fight to free Czechoslovakia. Lt. Geisler's other duties did not require him to join this force, but he insisted on doing so. He sailed that summer from England knowing that his child would be born early the next year.

The convoy steamed through the Mediterranean to Port Said. Travelling over land and water, to Teheran, the Caspian Sea and into the Soviet Union. The 2nd Czechoslovak Parachute Brigade troops joined the battle thirty kilometres north of the Polish-

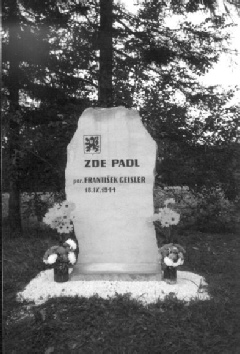

On September 18th. Lt. František Josef Geisler was killed as he tried to bring more of his badly wounded men from the battlefield. Four months later in England I was born.

This is the story of my search to find the father I will never meet: a search

that took almost fifty years.

In the final months of the war, my mother not only had to come to terms with the death of her husband, but also with motherhood. From a very young age I was aware of growing up without a father, and yet I became familiar with him through the stories I heard about his courageous acts. My knowledge came from his letters and photographs, and my English and Czech families, and from meetings with my father’s friends in England and Czechoslovakia.

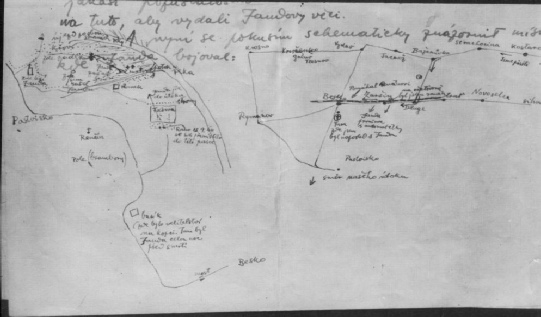

One particular friend, Dr. Jan Flax, had been present at the battle where my father died. He had written letters to my mother describing what had happened, including a rough sketch map showing the field where my father had been killed, the wooden farmhouse where his body had been taken, and the spot where he had been finally laid to rest. Again and again I read Jan Flax’s descriptions of my father’s last days, the heroic battle and his burial place. I grew up determined to find the place where he lay.

My parents’ Wedding Day

My father standing next to the hut, acting as ADC to General Sikorski 1941

When I was a very young child my mother and I lived with my father’s parents in Brno but when the Communists took power in Czechoslovakia in 1948 my mother and I left my father’s family and country for England. The 1968 Russian invasion dashed further my hopes of returning to find where my father lay but the rough sketch map was always in my mind, although the chances of my visiting that foreign field seemed less and less likely.

As an infant I had acquired dual nationality. The regime in Prague reminded me of my military obligation by calling me for conscripted military service. Any visit on my part to Czechoslovakia would ensure my speedy despatch to their ranks. I chose to remain as an officer in the Royal Tank Regiment of the British Army and as such it was necessary to relinquish my Czechoslovak nationality and along with it my obligation to do military service in the Czechoslovak Army. Politics and time had created the irony that I now shunned the army of my father.

Jan Flax’s sketch map in part of the letter to my mother in 1945

My mother, travelling on her British passport, visited our Czechoslovak relatives on several occasions, once going east by train and bus to visit the war memorial at Dukla. I listened as she described all that she had seen and heard. I held photographs of the bronze tablets marked with my father’s name. But where was my father? None of the official memorials or explanations correlated to the contemporary evidence of the battle so familiar to me since my childhood.

My paternal aunt had married a friend of my father. He too had been at the battle for Dukla. At their American home I learned much about my father; as a brother, as a friend; how he lived, how he died.

In the more open political climate of 1989 my mother and I planned a visit to Czechoslovakia and Poland. The changes of late 1989 meant that we visited countries free from Communist rule. We greeted friends and family -

Accurate maps of the area were impossible to buy, their availability was restricted to military personnel but not former officers of the British Army. At a border crossing high in the Dukla Pass I showed Jan Flax’s sketch map to a Polish Army Colonel. My hopes of finding my father’s burial place that day were dashed when he told us that Pastwiska was not a place name, but the Polish for potato field. We could go only to the other place named on the map, Besko, and from there follow Jan Flax’s directions to the South.

My father at the head of his troops in Windsor 1943

Our Polish visas were valid for one day only, and we had not realised that we needed a visa for each entry into Czechoslovakia. We had used our only Czech entry visas to enter Prague, now we had a problem, we could not re-

With President Benes

1941

Thus armed with the correct papers and buoyant hopes, we returned to the Polish border, where our British passports were promptly taken from us. After an anxious wait they were retrieved by the same Polish colonel we had met earlier. We crossed the border into Poland at last.

We found Besko. Jan Flax’s letter and sketch map became even more meaningful as we drove to the church and the church house which had been used by Dr. Igor Lomsky as the 2nd. Parachute Brigade’s medical station during the battle. With Jan Flax as our guide we drove southwards and found the timber planked farmstead like the one where my father’s body had been sheltered below its wooden eves. If indeed it was the same one, then the site of his burial must be just metres away.........but where?

We wandered the small hillside, desperate to find a clue or hint of a grave. An old farmer, speaking to us from the gloom of his dirt-

All sense of contentment and ease gradually diminished as weeks passed, and I compared my collection of contemporary evidence to the hills and valleys, mountains and passes I had seen and walked around Dukla. None of the evidence indicated that the wooden farmstead was not the one described by Jan Flax, yet my doubts grew.

In the summer of 1992, I returned to Northern Slovakia with my cousin Raduška, the Czech born daughter of Dr. Igor Lomsky and my paternal aunt Libuška. Raduška communicated her excitement to everyone we met. The hotel receptionist in Svidnik heard the reason for our visit from my bubbling cousin and arranged our introduction to the Director of the Army Museum in Svidnik. He knew of my father and showed a real interest in my story and we arranged to meet again after my visit to Poland.

Back at Besko we met more local people, and I became more certain that I had misread Jan Flax’s sketch map. I had not found my father. The meeting with Dr. Josef Rodak, the Director of the Army Museum, the next day was interesting, deep and punctuated by copious amounts of Russian vodka. Dr. Rodak studied Jan Flax’s map, but maintained the official version that my father’s body was taken from the battlefield at Dukla, to the mass grave for the 2nd. Czechoslovak Parachute Brigade at Nowosielce, in Poland. However he offered to provide a Polish/Ukrainian interpreter and personally accompany me to Dukla when I returned the following year.

Churchill’s visit to the Czech troops 1941

The next twelve months sped by. I had now come into possession of a military map -

Armed with this and every other document and piece of evidence, plus photocopies of Jan Flax’s hand drawn map, and even more anticipation, I set out for Svidnik again. Dr. Rodak studied all the documents, including Jan Flax’s letters, and retracted the long-

On September l7th 1993, accompanied by Dr. Rodak and a friend Jiri Štibingr, I again went to Dukla. Dr. Rodak engineered our prompt crossing of the Slovak-

We reached a nameless hamlet and were directed to a place that seemed even more remote.

Driving through an avenue of trees, Jiri spotted a sign — Pastwiska.

We stopped at a modern concrete house and spoke to a short, stocky man who listened to our story. He then took us to an orchard to meet a man who had actually been in Pastwiska during the battle.

This second man was gaunt and elderly. He spoke very slowly and precisely in both Polish and Russian, using deliberate gestures that added weight to his words. He had been a boy in 1944: he remembered the battle and led us to soldiers’ graves. I followed his footsteps across a field, walking with tear-

My father at the head of his troops

London 1944

Sad and alone I left the small ravine, and the trees, climbing to what would have been a small hill above the now flooded river valley, along the lake shore through a meadow that was knee-

Josef Rodak and Jiri, each armed with a photocopy of Jan Flax’s map had found another tree line, with its own stream-

Machine gun training

The next day September 18th, I was back in Pastwiska, with the others aware of my feelings I led them along the exact route drawn by Jan Flax but ignoring his map’s assumed scale. Because it had been drawn under extreme battle conditions, it was not surprising that in some places areas had been foreshortened and in others the distance had been exaggerated.

Eventually we arrived at yet another old timber farmhouse. A lady appearing to be in her 50’s emerged from a modern house built beside it. Josef explained the reason for our visit, saying only that my father was a soldier. She took us to meet her husband. She invited us into her sitting room for coffee and introduced us to her husband, a short, powerfully built farmer. He had been born and raised on this farm, and had spent his entire life working there.

He then told us this story............

Inspection visit

He had been a youth of thirteen when the first Soviet armoured assault was made. He recalled the battle that had taken place, and described for us how he had seen a Czech Army Lieutenant rescuing his wounded soldiers from the battlefield. The officer had been killed by German machine gun fire. The man remembered the officer’s body being put by the old farm building where it had lain for some days before Czech soldiers had returned, dug a grave and buried the officer themselves.

All that he said was as Jan Flax had described, in the letter he wrote to my mother forty-

The man led us to the place where the officer had been killed. Moments later we stood in the field where I had shaken with emotion and tears just a day earlier. We went back to the old farm house and from there he led us to the burial place. For years local people had remembered and honoured the grave, but as time passed and the memory of the war faded, so had the remembrance.

My only thoughts were that I had found my father, and stood close to him.

This account was published as a newspaper article in the Prague English language newspaper -

On the 50th anniversary of the death of František Josef Geisler -